DATA MAPPING CO-DESIGN & TESTING CHANGEUP

Services

Service Mapping

The diagram below maps services that are explicitly focused on the Early Action System Change priorities. It plots them against whether they are provided by the voluntary sector or public sector, and whether they adopt a prevention approach, or treatment.

“A system that doesn’t know itself cannot change itself”

Systems Thinking

Why do we need a different way of thinking to address complex social problems?

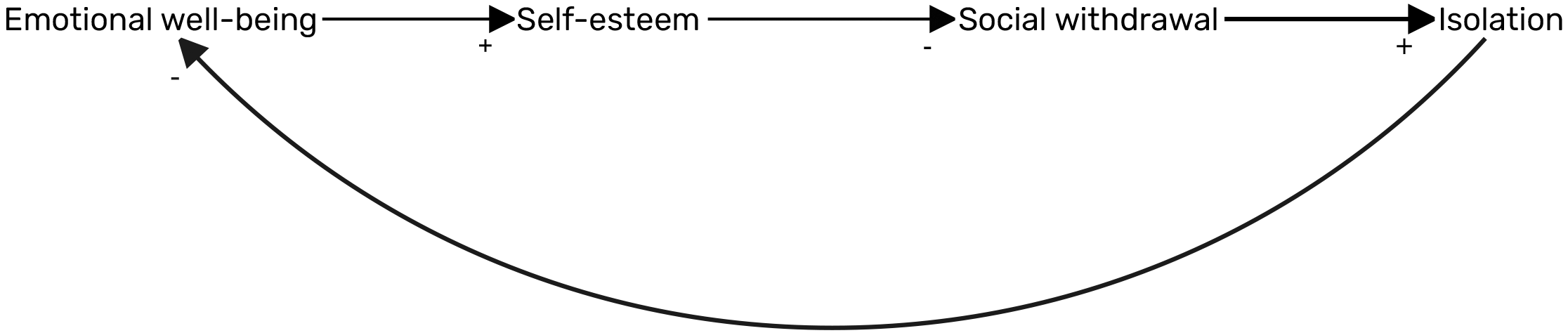

Linear thinking only tell part of the story (‘X leads to Y’).

To truly understand how systems operate, and to help us identify opportunities to address complex social problems, we need to think through the interconnected systems and feedback mechanisms or ‘loops’ that exist around the problem.

“Think Differently. Think Systems”

Applying Systems Thinking

Method 1. Insight workshops with managers, commissioners and practitioners across Renfrewshire.

Method 2. Rapid review of existing data evidence on drivers contributing to priority outcomes to sense check and enhance workshop participants drivers and loops.

75+ hypothesised causes and consequences of poor emotional wellbeing

45+ hypothesised causes and consequences of coercive control

A briefing report mapping the relationships between these causes and consequences will be made available once finalised.

“The most reliable indicator of system reform is change in the flow of public money”

“Complex Social Problems need multiple intervention points”

Expenditure

Financial Mapping

In the context of significant financial cuts coupled with rising levels of need, there have been calls for public services to prioritise spend on prevention and early intervention.*

We undertook a financial mapping to understand expenditure within children’s services in Renfrewshire.

The fund map report can be accessed here.

* Christie Commission on the future delivery of public services (2011).

Source: Twenty-One Lessons and Five Investment Opportunities (2015) Dartington.